About This Episode

This time around, we interview Stephen Phillips, CEO of Australian A.I. lab Mawson, dedicated to developing Artificial Intelligence software around music and audio, and home to Popgun, Replica and SUPERRES. This episode turned out to be almost an hour and a half long but, it would be a crime to cut any of it out. So, we've decided to split episode into two parts to make it a bit more digestible.

In the first part, we talk music recommendation and discovery algorithms and We Are Hunted, a music website founded by Stephen in 2009, that was first to use social media data to build prediction charts — and help dozens of labels discover talent in the process.

You can find the second part of out chat with Stephen, where we'll get down to the current Mawson's projects and the future of A.I. in music here

Topics & Highlights

07:55 — On starting We Are Hunted

Stephen Phillips: So we worked in the news for the first two years, and [...] in those two years, we built up the news site that became one of the most popular sites in Australia. And just because of that, Ben Johnson and Nick Crocker, they had this idea that maybe music ranking and music charts would be better done if it was based on social media, rather than record sales — which seems patently obvious now. But in 2008, it was a new idea.

David Weiszfeld: People have to remember YouTube was launched in 2007, and [at the time] Facebook had no [public] pages — it was the MySpace days. 2007 is not long for people like us but it's actually long for the Internet.

Stephen Phillips: We [thought] we can do a Billboard-style chart based purely on social media [...] There was an idea that it would be closer to real-time than record sales were, and it would be responsive to things that were happening in zeitgeist: things that were happening when people were on tour, or the MTV Awards or the Grammys — it would be responsive to what people were searching for [...] and talking about.

[...] At the time we were able to produce the first version of Hunted in [...] two weeks or something. We just had all the tools in place and we just needed to go out and find data, really. We just didn't think it was anything until we released it and it had one of those magical blow-up things. We released it on a Thursday night and Friday we woke up and everything was different. It was featured on Wired, it was featured on TechCrunch, which was the product hunter of the day, and my inbox was full of music people. People just loved it out of the gate.

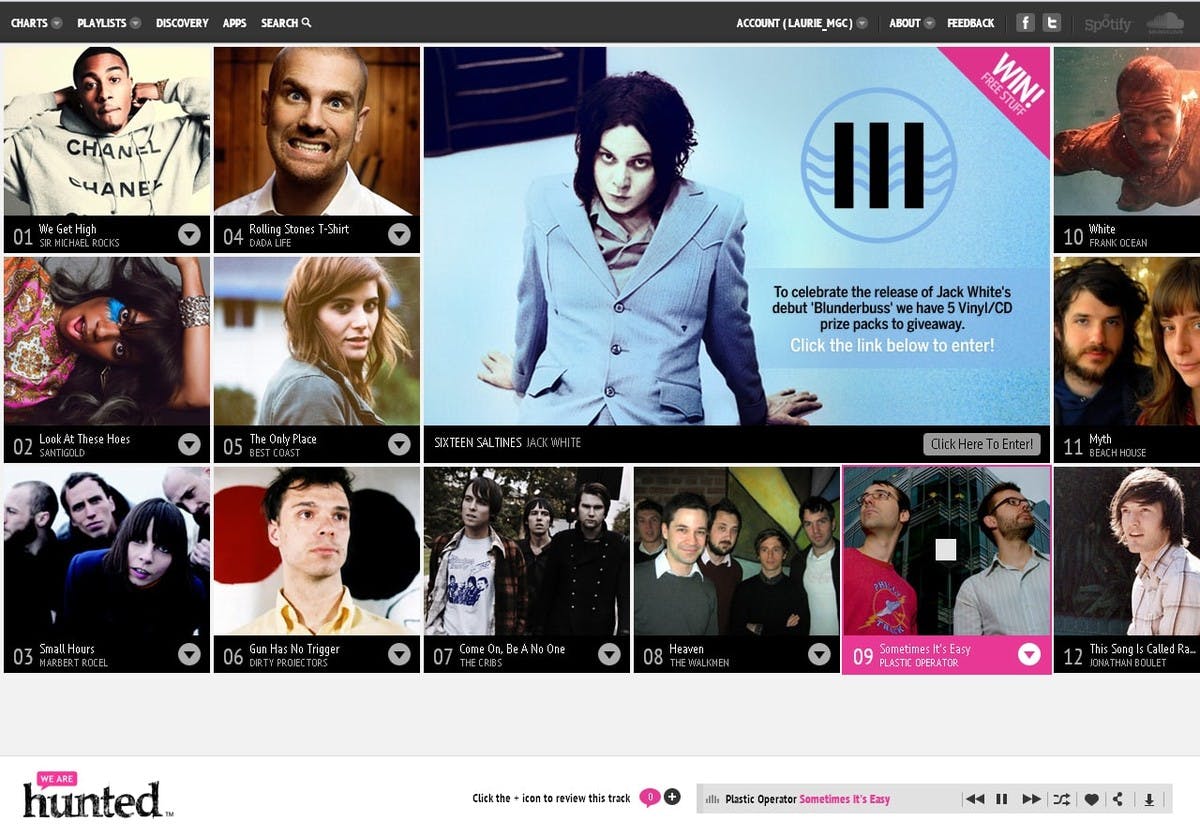

We Are Hunted Layout

13:22 — On Developing We Are Hunted

David Weiszfeld: So, everybody's finding value — more value than even probably you thought you had. [...] The Billboard of the New Generation, that must have been awesome — and especially in 2007. Today, everybody is kind of thinking about new charts and algorithms.

Stephen Phillips: For the first 12 months of Hunted's life we never touched the code again or did anything. Our investors were very cautious about what the music industry would do to people like us. They had no experience in the music industry, and neither had we. As tech-people, the only thing we knew was that [the music industry] were shutting down sites and prosecuting the founders of these sites. My investors were not up to that. We continue to do news for a year, but at the end of that year, we hadn't really grown the new site that much. We concluded that we had the maximum coverage of the market. There were only 600,000 people in Australia, who cared that much about financial news. And Hunted had already [...] gone past that in traffic.

The first big startup lesson I had was at that moment when I had to go to the board and say: well we didn't actually shut it down but we didn't work on it, and look what's happened to this thing that we didn't invest in, that we didn't do any work on. It outgrew the thing that we spent a million dollars on. We told ourselves that we would get sued and we hadn't validated that. That was holding back the growth of [We Are Hunted] — we were scared. So I had to work this out, [but] how do you work out if you're gonna get sued without getting sued?

David Weiszfeld: I was going to say — how do you test that assumption? You go and ask people: will you sue me?

Stephen Phillips: I don't know how the world works, man! But [...] within 24 hours [of that board meeting], I got an email from a guy at MTV, inviting me to go to New York to meet them. [...] I jumped on a plane, I met the MTV guys, I met the Sony guys and everybody was cool. They were very much "Ah! You're lucky it wasn't three years ago, but now we don't do that anymore. We're all over suing everybody and now we want to embrace technology and thank God you're here!".

22:18 — On We Are Hunted as a radio station

Stephen Phillips: At the time we had lots of ideas about what were the levers of growth for the site. It seemed to keep growing — but we weren't sure why or how. And then we kind of realized, after a bit of experimentation, that we thought we were this discovery thing but no — we're actually a radio station. [...] We could see that if we loosened the idea [that] this was a chart [to] this is more a music discovery experience, we would keep people engaged longer.

David Weiszfeld: Already the concept of a good song, a retention song, a bad song — it's really thinking like a radio, or thinking like a playlist-person at Spotify today. You had the ultimate flash finds playlist, so to speak.

Stephen Phillips: Yes that's right. You mean how do we measure that? What we thought was good? [...] It turned out it was a combination of three things. The first was we did canonically still have a chart, we knew what the most popular stuff was. We had an API that music companies were using [...] and we published monthly reports. [...] We combined it with two things. We found [that] there was something about the imagery that meant something to users too. We could tell what type of images people would engage with and how people would listen and discover with their eyes as well — which seems funny for a radio thing. But we knew [that if a] band had awesome-looking photos, people would immediately engage with it. Mostly it was [artists] who look really strange, or creative, or outgoing, or different. The second was [the] skip-rate. [...] We made it really easy to skip to the next [song], and we had a ranking based on which songs people listened right through to. I would say that's how Spotify does their stuff — it seems a pretty obvious way to work out which songs really are sticky.

33:11 — On predicting the popularity of music

Stephen Phillips: Two or three times [we’ve changed] the algorithm that powered the chart. [...] Version one was all about aggregate scores of mentions or deltas of change in a number of mentions across time. [...]. And then [...] in the third version, which was the version where we went from 1,5 to 8 hours of [average session length], [we realized] that actually we're measuring the wrong thing. Everybody thinks we're measuring music, we're not! We should be measuring fans and that we should find those who have the best taste in music. [...] When I say best taste [I mean] which ones are able to predict what's going to be popular a month from now.

So the site completely changed, it was all around not caring so much about what people were saying on music but WHO had the best taste, WHO is best able to predict the future and what were they listening to today. [That were] really early ideas around influences in the music industry. At the end [...] there were about 60 to 80 people in the world who were the best at predicting what was going to happen next. [...] That group of people was in flux all the time — now these people now have the baton, they're the cool kids, and they're the ones who are deciding what's going to be popular. But overwhelmingly, [when we found those people] most of them worked in the music industry. There were moments where we realized perhaps we're just measuring a game system. These people are the people who make the music and therefore "are we eating our own dog food here?"

David Weiszfeld: We act like a self-fulfilling prophecy. You're speaking to a person, he doesn't know but he is feeding the algorithm himself!

Stephen Phillips: We kind of felt like we've just really uncovered how the music industry works! These people who were promoting it, they're the ones who made it. Now they're good at predicting it because they made it.

46:30 — On the Twitter deal

Stephen Phillips: When the acquisition come, when we were negotiating price it was all about headcount — because it was really an acquihire. [Twitter] wasn't interested in keeping Hunted alive. They wanted the biggest engineering team they could have, who knew something about music tech. They said it multiple times: we think we can build music charts ourselves, but people might not believe it. If you come in and build a for us — everyone will believe it. [...] When they launched a competitor to Billboard — which they didn't in the end, they did integration with Billboard — [...] their whole idea was to get musicians to equate Twitter activity with success. So, let's do a chat!

And it made total sense to us as well. And we liked that it was the acquihire, they wanted the engineering, which was their main attraction but there was also some value that we're getting out of Hunted — if only credibility. [...] This is probably how the story ends. It was literally in 2012. We've been going since Hunted has been alive — since 2009. I started in my garage in 2005 so it had been seven years and since that time I sat in the garage, my wife talking about it, to being in New York and selling to Twitter. [...] And, you know, by then the music industry — I only ever had really positive experiences with them. They used the site, loved what it did, found artists [...]. Yeah, I just didn't have any negative experience with [the industry] at all.

Listen as a Podcast

Companies Mentioned (in Alphabetical Order)

Full Transcript

David Weiszfeld [00:00]: All right. So hey everybody. We're here with Stephen Phillips. Stephen is currently the CEO of Mawson, that is an A.I. lab based in Australia, who is focusing on entertainment. Graduates from the Mawson lab are Techstars alumni Popgun and current state Techstars companies Replica and SUPERRES. Previously Stephen — and this is how I've come to known Steven, before actually knowing Steven — was the founder and was running the popular music discovery website and platform called We Are Hunted that people just called Hunted that was sold to Twitter in 2012. I loved Hunted, and I was blown away by a demo that I saw Popgun last year, when I met Stephen for the first time, and I can't wait to see what's coming next for those A.I. music companies.

So let's just jump into it. Most people kind of know you for Hunted and everybody is starting to know Popgun pretty quickly, but most people don't know that you are one of the you know like one of the top engineers, definitely, in music out there. And I'm very interested to understand how did you start being confronted with computers, with code, with building things. It's such a specific thing that you started to do — I think it would be inspiring to understand a little bit more of the background.

Stephen Phillips [01:27]: So, I grew up on a cattle property in far northern Australia. Pretty remote area. My father had been in the Air Force in Vietnam and he had worked on mirages, and had become — well we had horses and pigs and cattle and stuff like that. His hobby was making things and put things together. He had computers that he was fixing. He didn't really know what they were for, but he was making them because he was into electronics, and at about the age of ten — I remember he fixed the VIC 20 and I started programming on a VIC-20 and then on Commodore 64 and then on Amiga and then early PC and Macs. So from about 1982 onwards I was programming. I did really poorly at school until 11 and 12 when I was sent away to Canberra, which is a capital city in Australia, and I attended a science school for underperforming kids — I think it was. Not sure exactly why I was selected to go to it. But I met all these I met all these people who felt like my tribe and I realised that I need to study so I can hang out with these people — not the people I was kind of going to school with. And I studied hard and grade 11/12, I did very well, I got into medicine, and I left North Queensland and went to Brisbane, studied medicine for two years.

It took me two years to realise that I shouldn't be doing medicine. I didn't like people that much and I particularly didn't like sick people, so I decided I wouldn't do that. My parents weren't happy with that decision at all. They decided to not support me, so I had to get a job. I got a job with the only skill other school I had which was programming. So this was in 1991/92, and in those days programmers were third class citizens of companies. I went along without any qualifications but I could kind of been coding for 10 years or more and got a job and then started earning what 100k is a 21 year old running software teams. I eventually within a year was running teams and so all the way then from all through my 20s. I was working first doing software development in VB, and then dot-net, and then doing web stuff, and started to build websites, working for agencies — working in building websites for hire, basically, and I worked on hundreds of websites as people do within agencies. Small ones, big ones, I worked on front-edn and back-end, design, middleware stuff, payment integrations — all different types of projects all through my 20s, until mid-30s.

I got kind of sick of that and wanted to do my own startup. I lived through the dot-com one boom and watched that kind of from the sidelines. Being on the wrong side of the fence. Getting paid to build sites for people who were having their shot at stardom — always kind of envious that I'd never worked in a startup or had a chance to do that. And then I got a chance — not really a chance, I just decided with my wife and I decided to do it when we were 35, something like that. We decided that this was now or never. So I just started building a startup, literally in my garage nighttime, weekends. And even back then I was just always fascinated by the idea of wisdom as a crowd, such stuff with the Internet. What could we learn from processing what people were saying on the internet about things. And the first site that I built for myself was essentially a news site, that aggregated news that stock market and tried to predict what we're going to be the most talked about companies and therefore what the most active stocks would be. I had no particular experience in finance that just seemed like something that people might find useful.

David Weiszfeld [05:44]: I was going to say, at this point after working years essentially almost as an independent developer — if you're working for an agency you're going right, left, different projects: small, big, good ones, bad ones, well operating companies, bad operating companies, working with extremely good tech people, and sometimes finding a very bad internal team. You learn a lot. It's kind of like working in a major music company or something you work with so many artists, so many releases — you're a bit more more low touch, but actually you're confronted by a lot more realities, and you can judge and understand where what types of company you would want to build and what types of company you probably didn't want to build. I had no idea you did this thing in the stock market and that is almost a great segway to Hunted: listening to the noise and listening what people say to predict what would be the trend. Can you segway into Hunted? At this point, hod you worked on any music website at the agency?

Stephen Phillips [06:41]: No. I'd played I played guitar in bands and stuff in my early 20s. I played music. Never done anything in tech around that. The Hunted thing was a complete chance. I met, about a year into working out of my garage, I'd got to maybe ten or twenty thousand users who were using the site, regularly. And then I had a chance meeting with an investor who — the timing was perfect. The synergy was perfect. He was one of the Australia's which is richest men. He was just leaving. He was one of the winners in the dot com-one. He was. He took his company public. He was leaving that company, and he just wanted to invest in startups and do new things, and I met him literally the day that happened. We had lunch and we really hit it off, and he said he wanted to back me in what I was doing and he was. I didn't know it at the time but he was very interested in news and he was hoping to establish a news presence in Australia. He's very progressive, left wing kind of guy and he just decided to work with me and he gave me enough money that I could go out and build a team. So we worked in the news for the first two years, and the Segway and Hunted was in those two years, we built up the news site that became one of the most popular sites in Australia. And just because of that, these two guys, Ben Johnson and Nick Crocker, who were in Brisbane, they had this idea that maybe music ranking and music charts would be better done if it was based on social media, rather than record sales — which seems patently obvious now. But in 2008, it was a new idea.

David Weiszfeld [08:32]: People have to remember YouTube was launched in 2007, and probably Facebook had no pages — it was the MySpace days. 2007 is not long for people like us but it's actually long for the Internet and that stuff.

Stephen Phillips [08:47]: We think we can do a Billboard-style chart based purely on social media. And people were like is that a thing? How would that work? Is that possible? And we were like, well I don't know. We'll find out if that's possible. And it had lots of interesting properties because it didn't solve the cold start problem, but there was an idea that it would be closer to real time than record sales were and it would be responsive to things that were happening in zeitgeist and things that were happening when people were on tour or the MTV Awards or the Grammys or — it would be responsive to what people were searching for, and looking for, and talking about, and — so I had lots of attractive properties. It was just at the time... We were lucky that we had done nothing but blog and text aggregation, indexing, named entity recognition, search, ranking algorithms for two years. So when these guys said it was like yeah, sure like how hard? Surely, this is easier than doing the stock market.

Turns out it's very different to in the stock market but at the time we were able to produce the first version of Hunted in... I think it was in like two weeks or something — and release it. Because we built, we just had all the tools in place and we just needed to go out and find data, really, and we just didn't think it was anything until we released it and it had one of those magical blow up things. We released it on a Thursday night and Friday we woke up and everything was different. It was featured on, there were articles on Wired, it was featured on TechCrunch, which was the the product hunter, I suppose, of the day, and my inbox was full of music people, and people just loved it out of the gate.

David Weiszfeld [10:27]: Did you work for an agency for the launch, or did you literally switch from the tech to the — because you had the tech website, that website was already known, locally — you switched the music and what happens? Like, literally one day you launch and you send an email. Do you have people in the US are speaking about you.

Stephen Phillips [10:44]: So Ben brought the design. So we had all the engineering, Ben bought a design, which is essentially a static screenshot of a grid, as in "we think there should be a grid with the artist face on it, and you click on the face and it plays". That's the design. I mean like, sure, that makes sense to us. And Nick who is now a partner at Blackbird in Melbourne, he broadcasted to a bunch of music people, and it just took off from there. There was no fanfare, it wasn't something we thought "oh, the world's gonna love this" — it was literally like "I hope this isn't embarrassing" — was kind of the... We knew it was good, because people really, immediately resonated with two things: one, the idea that you could do this with social media, was the first thing. And TechCrunch had the, that was the first coined the phrase — the headline on their article was "We Are Hunted is the Billboard for the new generation" and we were like, yeah, that's totally a great idea! We should have a position just like that. And I've since met the people that wrote that, and they just loved out of the gate too.

And the second was music people were saying this is real. As in there is something in this direction, because this feels more like, because they were looking at charts based on record sales, and everybody is stealing music. Therefore these charts aren't right anymore. This was the first thing in a long time. They said that this is what I thought was popular too. This is what I thought was cool. So we kind of felt we were onto something, and you know there's a saying around product market fit that if you know if you're not sure you've got it — you don't have it. Like it was instant, it was like people love this, and we have to kind of keep doing this. Whatever this is is much better than the thing we were doing. Because we invested lots of time, and we knew that it was Australian-only, and there's a limited population here. And this was this was people reaching out from all around the world. It was in the hundreds of thousands on launch day, on accidental launch day. And, yes it was just one of those things where. I'd been involved with hundreds of sites launching them, and nothing had ever done that. And I'd heard about that but I'd never lived through that before. I haven't lived through that since, to be honest I was I think that it was immediately loved.

David Weiszfeld [13:06]: I think you're right. The thing is, right, if you think you might have product market fit, you definitely don't. It's one of the things, the day you do — it feels like the lottery, I guess — and everybody just tells you. You get emails, you get messages, you see the traffic, people are sharing it. Everybody's finding value — more value than even probably you thought you had. And I love the way you said that the Billboard headlines. You and I are like non-US people and I guess they have the science of... We speak with very long sentences to say very short things, and sometimes those guys can nail a five-word punchline, that we wish we would have found. The Billboard of the New Generation, that must have been awesome — and especially in 2007. Today, everybody is kind of thinking about new charts and algorithms.

Stephen Phillips [13:55]: I think it was like very early 2009 was that we actually got released, with the company that has been around for two years working on news before that. And then throughout 2009, we didn't do any more work on Hunted. So for the first 12 months of Hunted's life we never touched the code again or did anything. Our investors were very — not unhappy, but very worried and cautious about what the music industry would do to people like us. They had no experience in the music industry, and neither had we, and as a tech-person the only thing we knew was they were shutting down sites and prosecuting the founders of these sites, and my investors were not up to that. They didn't think that was a good idea. So we didn't touch it. We continue to do news for a year, but at the end of that year we hadn't really grown the new site that much. We concluded that we had the maximum coverage of the market in Australia. There was only 600,000 people in Australia, who cared that much about financial news, that they would do this. And Hunted had already — without touching it — had gone past that in traffic.

And we knew that there was something her, and the first big startup lesson I had was at that moment when I had to go to the board and say: well we didn't actually shut it down but we didn't work on it, and look what's happened to this thing that we didn't invest in, that we didn't do any work on, and it outgrew the thing that we spent a million dollars on. We had told ourselves this fact, that we would get sued and we hadn't validated that. We hadn't gone out and tested that hypothesis. And this was a thing that was holding back the growth of this thing — that we were scared. So I had to work out what was... How do you work out if you're gonna get sued without getting sued?

David Weiszfeld [15:48]: So I was going to say how do you test that assumption? You go and ask people: will you sue me?

Stephen Phillips [15:54]: I don't know how the world works, man! But I remember I had the meeting, and we decided I had to solve that, and I think literally within 24 hours I got an email from a guy at MTV, inviting me to go to New York to meet them. It was like as soon as we'd made the decision to explore this, the world aligned an outcome is this email. I went to New York — I'd never left the tribe before — I jumped on a plane, I went to New York. I met the MTV guys, I met the Sony guys and everybody was cool. They were very much "Ah! You're lucky it wasn't three years ago, but now we don't do that anymore. We're all over suing everybody and now we want to embrace technology and thank God you're here!". So, my first trip to New York was amazing, we were treated like rock stars and somehow, the fact that we'd taken all of our contact details and went into hiding for a year created this mystery about "who are these people". Because the site was automated, it just ran itself anyway. It was just sitting on social media and then creating a chart and it would update itself every 12 hours with this music chart and it wasn't. And we did no press, and no one really knew who we were, and I didn't mean I had those guys New York found out who we were.

This is funny when that's happened a lot. I'm sure you've done the same thing where you decide to go in a certain direction and things line up when it's meant to be. And those meetings all lined up, and then, literally a month later, we decided to move the company from Brisbane to New York. No one cares about us in Australia, and that my total sense because the music industry is in L.A, in New York. And, back then, much the label's headquarters were in New York. So we moved to New York to be closer to the action. And just to explore where this would take us, we were still — still no particular plan, because we had... You know, this was a site that was having millions of users, and we were just basically sitting on top of SoundCloud API. We had no way of legally monetizing the site. We were even unsure exactly if what we were doing was legal, because we weren't sure if SoundCloud knew whether what they were doing was legal either. So it was like a whole crazy house of cards. So I had all this. The site was incredibly popular and continuing to grow, and people loved it, and we released versions, and Twitter was in love with it, and all these label people would reach out: "now we're using it for A&R". And I had this successful thing but I had no plan. How do you monetize this thing?

David Weiszfeld [18:31]: Everybody was using it, so either it was music lovers going to discover the website — and I know some of the numbers on the number of hours per day, and are mind blowing. Maybe you can go over that a little later. A lot of a A&Rs, and agents, and anybody working in music was kind of keeping an eye on it, because that was the quickest chart — the artist would appear there first. It would be the trends that you would see maybe later on elsewhere. But you guys actually never really monetize the website you had sometimes of this thing in the middle to advertise a pusher, but that was more like free a free advertising that you would give people. So at this point you're in New York, you have the funding, the website, the traffic is going up, the sessions... I think what is it, eight hours per day or about four hours per day? But crazy-long sessions. The market is looking at you, and obviously you kind of realize that you started this news site, that became this music site, that became this juggernaut. What's the thinking process? You're literally in the middle of the music industry, while a couple of years earlier have never really worked in the music industry. What's going through your mind and and maybe a segway to the exit story at Twitter? What makes you think alright this is the end of the cycle? Let's do something else, let's change, let's leave the company?

Stephen Phillips [19:50]: So in New York I was just totally obsessed. I was totally obsessed about solving the "What is the business model, if you've got a music discovery site, that has these loyal fans who are spending a long time on the site"? And clearly people enjoy what it is. But, I don't own the content. And the people I'm streaming it from, I'm not sure they know who owns it either. And that seems really unclear. What is the plan here? And I didn't know the music industry well enough to work out what the path was. So, I spent months, and I had a funding crisis my own. Investors... I hadn't signed up to do a music site. This isn't what — it was easy to monetize the news that we'd won contracts with banks and organizations who were paying for. But who's paying for this music thing? I'm sure it's treble whatever the traffic of our news thing. But how does this end? They had no experience and they basically pushed it back on: "we're not funding this anymore, because this doesn't, we don't understand where this goes". So you have to find... And this wasn't a bad moment. This was going to mine early investor in saying I think this is really important. I don't understand it you don't understand it. We need a strategic investor who does understand it. So I had to try and make music investors, and understand what would you do in this case?

And a lot of people had ideas of what to do and I did end up meeting guy in New York, who — he had a very clear vision for it. And he was the first one who was able to articulate, and he was the first one and kind of showed me that Hunted wasn't a music discovery site — it was a brand that meant "cool". And you can do a lot with that in music. You can, you can have merchandise, or you can run festivals, or you can go into colleges and he had a vision for it. He was just a random guy I've met through a bunch of intros, and he sat down and laid it out. And he showed me that I was just thinking way too narrow about what we actually had, and that this was just a way you built up equity in this thing. That was the people really connected with and you could monetize that in other ways, rather than directly with music. And how much music is about the brand and the personality and things like that. The time on site stuff was strange like, for the first year in a bit, we didn't really know. We had lots of ideas about what were the levers of growth for the site. It seemed to keep growing but we weren't sure why or how. And then we kind of realized, after a bit of experimentation, that we thought we were this discovery thing but no — we're actually a radio station. And we're just a very cool radio station, that changes every day. And that there was another metric, and so we said basically if that's true, we started measuring time on site and we went from my 20 minutes to 40 minutes and over the course of about 18 months we drove it up to about 8 hours. And we've worked out how to reorder the chart. We were less concerned with the idea of this is a chart to we have to... A chart implies that the music is getting worse across time. So we didn't want that, because we could see that, if we if we loosened the idea this was a chart and this was more a music discovery experience, we would keep people engaged longer — like they would tolerate. I can remember what it was, when we ran experiments, where people would tolerate one bad song every three or something.

David Weiszfeld [23:26]: Hunter was all about social popularity. So, already the concept of you guys thinking that this is a good song, and like a retention song, and this is a bad song — it's really thinking like a radio, or thinking like a playlist-person at Spotify today. You have the ultimate flash finds playlist, so to speak.

Stephen Phillips [23:46]: Yes that's right. You mean how do we measure that? What we thought was good?

David Weiszfeld [23:50]: Yeah I mean obviously you, you knew when people were leaving the website, so I guess it was more of an objective metric — like a bad song as a song that people skip. It was not like a bad song as a song that Steven Phillips doesn't like.

Stephen Phillips [24:02]: Yes, that's right. It was it turned out it was a combination of three things. The first was we did canonically still have a chart. We knew what the most popular stuff was. We'd honed that technique pretty well, and we had an API that music companies were using, that was the actual chart, that they could use. And we published monthly reports, or something like this on the site — where we publish the real data. But we found that there was a big drop off after you got to 20 or 30 or something like that. So we combine it with two things — once, we also found, I think you and I talked about this. There was something about the imagery and the song that meant something to users too. And we could tell what type of images people would engage with and how people would listen and discover with their eyes as well — which seems funny for a radio thing. But we knew that certain, a certain band who immediately had awesome-looking photos, that people would immediately engage with, and stop their radio station experience with that. And mostly it was just people who look really strange, or creative, or outgoing, or different. And the second was we measured skip-rates really high. You know the people would make — we made it really easy to skip to the next one, and we had a ranking thing based on which songs people listened right through to. And I would say that's how Spotify does their stuff. It seems a pretty obvious way to work out which songs really are sticky. We didn't have to have it personalize, because we had such aggressive turnover that it wasn't like "we created a chart just for your experience, just for you". We did have a section inside that did that, we experimented with personalization but, overwhelmingly, it was the main chart the people enjoyed the most.

David Weiszfeld [25:45]: I guess it's kind of if you're turning to your favorite cool radio, you kind of expect them to have an editorial view that they're going to show you, and you go there to discover new stuff. There's a place for personalization and Spotify is showing the way on that, but a pure editorial recommendation is still extremely strong in the world of music. Probably 95% sales of a recommendation, if you take away the Discover Weekly / Release Radar. Few playlists are starting to get personalized on Spotify, but the big majority across DSPs is editorial. People are frozen in front of too much choice. You should give them a choice from 10 things they're going to take what they want they usually know. So when you go to a music discovery — especially if you don't know what you're facing — you kind of expect it to be pushed to you. Yeah, the thing about the photos when we discussed it I thought was fascinating. And actually when you were seeing it just up it's the same thing now on YouTube. There is the the video is on the right side and you're watching a video, and the YouTube people, like the best practices are: changed a preview image until you see that you have a bit of an uptake. Some images are more clear, more dark, more colorful. You can have the text on the image — like typical YouTubers will have their face and then some kind of big tittle on them. And that I guess, if everybody's doing the same covers today, it's because there's a general consensus that on YouTube those covers are way better than just a still or screenshot of the of the actual video. You guys were basically using a lot of portraits, and every band had their identity, but somehow the website looked like it had a branding like it is not random photos of any band. They had their faces, that were more like a header of Spotify than a single cover.

Stephen Phillips [27:34]: And that was very much a design process as part of editing of songs and artists making onto our chart. There was a designer called Adrian, who went with us to Twitter, and it's now it designer Lyft. He was the curator of all of that and he was a he was a nazi about the types of photos that would make it to the site. There was a style to that and we just appreciated some feedback on the site, especially because we were competing with Hype Machine, who was much more text-based, or they had a different layout to us and ours was very visual. So we really wanted to go down that path and make that a clear... And we also got, because we got so much feedback from design agencies, who were using the site and now we're using it broadcasting across the whole company. And we know that they appreciated that design stuff like that as well. The other people who are doing it really well, you see the Netflix is doing the same thing. And their interface is very Hunted-esque. As in I don't ,want to say that we inspired that but it's the same idea that they get. They change the image of it to appeal to you to go and watch that show and they're finding headshots and stuff, and dramatic scenes in those things, and I'm sure they're doing the same testing as well.

David Weiszfeld [28:47]: The last thing Netflix wants you to do is search, because that means you're kind of looking what's repertoire they have, what they don't have. So if you search and they don't have it they recommend another movie from the same actors. They're very smart about that. But it's basically a browser experience, based on what they think you're going to like, what you've watched before, things that you started watching, new episodes, and it's kind of pushed into a recommendation engine, rather than a search. In order for it to be a search you need to basically have everything.

Stephen Phillips [29:16]: I think it was also something to do with the users too. We concluded there was about — back in 2011, when it was at its peak — that we were maybe having three or four million users and we thought there was about 10 million of them in the world. So 10 million as in "these are people who care so much about music that have to be first, and they have to know what's cool before everybody else does". So they weren't wanting a personalized experience too. They prided themselves on having a depth of knowledge of new music, so they wanted to hear it all. And even as I went into that particular thing, or they didn't like that style — because of who they were and music was such a part of their identity, amongst their peer group or whatever — they had to know all this stuff. They were happy to consume all types of stuff. They just wanted to be current and new, so the currency we sold was freshness and coolness type of thing. That was a huge priority for us. We had to be first because that's what we felt our audience wanted. They wanted to get it and see it, who ever saw it.

David Weiszfeld [30:25]: I find it interesting as well you mentioned Hype Machine and a lot of competing companies want to compete and do the same.We're going to do the same but a little bit faster or save a little bit better. You guys were literally doing completely two different visual experiences. The idea is using the website for music discovery. The ways you're doing it are different and we don't have time here to go into the way they do it in the way you did. But the layout and the experience is completely radically different, and you create a lot more emotions with the users. If you have your real identity rather than we're both the same and people can't really know. The website of Hunted is still very contemporary today like people are still building websites. You had the lateral scroll if I remember instead of the vertical scroll, that I saw on a website a few months ago and it still looked cool it still looks different.

Stephen Phillips [31:20]: Jess had just about design version 3 and Hunted like that. She comes to us with that, and everyone's like "Are we really going to do that horizontal scrolling?!". The developers we're like; everybody hates horizontal scrolling sides but at some level we just kind of felt "No, fuck it!". Like if we can, who can do this? So it'll be different everybody else let's do it and people loved it when we released it. We polished the hell out of it and the guy who did that JavaScript craziness so that it would scroll on your mouse and accelerate you got to the edge and all this stuff. We like that over that stuff so hard for a week or so just to get it because we knew people are going to hide it and it had to work perfectly all browsers write off the guy so that you could have this continuous filing of new music thing. Anyway, it worked pretty well. We've never gotten here like publishing I think we're still at six seven. We knew we were competitive but in the end I felt like, we were just in a different discovery experience. I'm sure people use both but most of the feedback we had were from creators and staff who were not at the extreme end of the music like they don't want to talk about the music they just wanted to consume it. That's been around years before us and now it's still around now. They outlived us. They started before us. We never got near their numbers.

The other thing was interesting was how which I've learned a lot from was because we had those metrics. Took us a while every month to discover what those metrics were, about what was the levers of that were actually moving the site. It allowed us to actually change two or three times what the algorithm was, that powered the chart. It wasn't just changing the math of it. It was more like we changed conceptually what we thought music ranking should be. I remember the version one was all about aggregate scores of mentions or deltas of change in number of mentions across time — like really traditional approaches to how you would measure with the most popular thing is. And then we kind of moved off on that and we realized that mentions or listens aren't equal. And some people had better taste than other people and we should be taking that into account. So we saw the weight mentions and depending on who mentioned it they had more weight than others. And then we kind of realized in the third version — which was the version where we went from like an hour and a half to eight hours — was the big breakthrough for us was realizing, that actually we're measuring the wrong thing. Everybody thinks we're measuring music, we're not! We should be measuring fans and that we should find who has the best taste in music. And we developed an algorithm around that. As in, all of the people who are talking about music now, which of those have the best taste. And then when I say best taste — which ones are able to predict what's going to be popular a month from now. And because we had two years of data about what people were listening to, and what happened on the major charts like on iTunes and Billboard, we knew who was best at predicting it.

And so the site completely changed, it was all around not caring so much about what people were saying on music but what the WHO had the best taste, WHO is best able to predict the future and what were they listening to today. And we saw just explosion of time on side around that, which is really early work on — and it eventually led to the Twitter stuff — Really early ideas around influences, and who is actually an influencer in the music industry. In the end, I can't remember the numbers, but I remember we looked back and, there was about 60 to 80 people in the world who were the best at predicting what was going to happen next. And when we will occasionally dig into those people, and we loved the idea because that group of 50 to 80 people were in flux all the time; as you'd expect. Like these people now have the baton, and they're the cool kids, and now they're the ones who are deciding what's going to be popular. But overwhelmingly, most of them worked in the music industry. There were moments where we realized perhaps we're just measuring a game system. These people are the people who make the music and therefore "are we eating our own dog food here?"

David Weiszfeld [35:57]: We act like a self fulfilling prophecy. You're speaking to a person, he doesn't know but he is feeding the algorithm himself!

Stephen Phillips [36:04]: That's right. And we kind of feel like we've just really uncovered how the music industry works! These people who were promoting it, they're the ones who made it. Now they're good at predicting it because they made it. So, we were in New York. I'll talk about how the acquisition happened. We didn't really look for acquisitions We'd been approached. We just didn't understand how that happens. Like it sounded like black ops to us. So you'd heard of companies being acquired, but it didn't feel like something that was possible, because we didn't make any money and we didn't understand!

David Weiszfeld [36:41]: Who to call like "hi Twitter, I want to be acquired!"

Stephen Phillips [36:45]: That's right. Because we'd run out of money, to keep the team together and see if we could work out how to find investors to take it forward, we were doing work — we were guns for hire — We were doing work for Sony, we built MTV staff, we worked on MySpace, we did a project with Microsoft. So we were well known in that space. And, you know, that contributed a lot. So two things contribute to the acquisition. One was, big companies knew who we were — building great stuff and doing it quickly. And the second was, as soon as we started to rise and we then found funding and went down that path. That triggered a whole lot of urgency around: "Look if you're going to get them you've got gotta get them now because they'll be off the market for two or three years". So, you know, a lot of that acquisition talk started to come out of the fundraising process as well which I believe is not — and I've been on the other side of the fence now at Twitter and the M&A — that's not a coincidence, that's part of the process. It just accelerate because they had been watching us for six months or more and hearing that VCs were now ready to invest in the company and take it forward triggered them to make a decision — or, at least, triggered them to make an approach to see how serious we were. And so the acquisition came pretty much out of the blue. One of the guys at M&A at Twitter just contacted us and he'd been running a project for six months or more to acquire a music company to help build Twitter music which was a project he was running. He came to New York and saw me, said "This is what we're going to do". This is something you're into and we're like "yeap, sure!".

This is as good of an exit ending to this story as I could imagine. It had been a lot of work and a lot of kind of emotional stuff to move countries, to move young families. My new investors were kind of umming and ahhing about whether they wanted to follow on with the new investors. Again, they still didn't know anything about the music industry. Why would we invest alongside these American dudes who are in the music industry, and we would rather if we could. So when I said look: these are the options, we can continue bringing new investors going on this new adventure or Twitter's six months away from an IPO that made an offer — we can swap our stock for theirs. The investors were like, there's no answer, we have to go. And everybody was kind of happy with that. This is probably how the story ends. It was literally in 2012. We've been going since Hunted has been alive since 2009. I started in my garage in 2005 so it had been seven years and since the time I sat in the garage my wife talked about it to being in New York and selling to Twitter. The process after that was Richard, who was my co-founder. We left New York. We're both living in there within the eight months that we went to San Francisco. We met the executive at Twitter, Dick Costolo, and a bunch of other guys. We had to pitch what we were and what the company was and I was super nervous to do that pitch. I don't know why, what do you pitch at this point? Hey, I got this thing, people love it! I don't know what that is!

David Weiszfeld [40:25]: And I was going to say it's very counterintuitive. When you're in the process of being in an acquisition, you're meeting people that are maybe not the first person you're speaking to from the company. And so then you have to re-pitch your business to people and when they've been the one reaching out to you, you're like wait why are you guys interested or am I supposed to pitch again. What's this?

Stephen Phillips [40:46]: I think they wanted to just know. I mean, they knew more about me, and they knew more about us and what we did, than I could have told them in the pitch. It was just like I think that just wanted to just say we were human and and how we would handle that situation of being because I think it was a head up I remember walking to a boardroom is full of these dudes who I'd read about and being intimidated by it. But just thinking well, you know, surely this was meant to be. This is how this story ends I'll just tell them the story like I'm telling it to you now. I leave a lot of it. There's nothing I can do. I can't lie about it. There's nothing I can say that's going to change their opinion. And I just, as you learn when you go and meet these people, they're just dudes, right? They ain't being honest and not selling, just being totally humble about what you've done and what you want to do next is the answer every time, and we just immediately clicked like, they already knew, they've already made the decision. They were just trying to assess how whether it was a good fit, whether this is something we really wanted to do and the circumstances around that.

From that moment they started talking to us, I don't think it was ever a moment where we thought " oh, this is going to fall through". It was like in the first five minutes it was on and that was it. It was never — Kevin who was the guy I was negotiating with. You know, they went through diligence on the tech and I went through diligence on the team and they had to get visas and it wasn't easy. We had to negotiate on price and do all this stuff. But it was never a threatening thing like it was always like, they made us feel like we were like — Twitter was an accident, somehow as well and you know their story is very similar. And there was also, they were going up to an IPO so, everyone was very excited at Twitter. Everyone knew that they were back then in 2012, there was this feeling that they are going to be the next Facebook or this could be anything. There was a very positive vibe around the company — I don't know how it is now, but back then they were like the voice of the Arab Spring, and they were rescuing children, and there was a real positivity about it. It was just a very easy thing to do.

David Weiszfeld [43:03]: 2012 is way before any social media backlash any kind of Facebook/Cambridge Analytica. Six months before going to a company that goes into it next six months before an IPO it is an amazing time if you're if you're at a startup that's when they're most people on the executive board we're probably there for a little while and they knew that something great was going to happen for them and for the company as well. It's a much different thing to be acquired in an M&A that is more of a merger of two competing companies or in a down market where there is consolidation. You guys were literally the music arm going in this IPO company. Even if not making revenue from everybody looking from the outside, you guys were company going up with traffic and discovery, very central and especially in 2012. Twitter was about verified badges, verified artists, ambassadors, influencers and that was a great strategic fit in between the two companies. I know there is a company called Hydric today that is almost a spinoff from some of the people that Hunted some of you guys went into the company and that was some surprises also after you got in. Could you tell about this? Nobody really knows. It's pretty rare for a company to almost spit it out right before it's acquired.

Stephen Phillips [44:30]: Well we weren't that big! People didn't know how big we actually were. I can't remember how many, maybe max 15 people at one point. There was a core of that 8 to 10 at any point. We had contractors a lot to come on and do. This was Hunted kind of the third or fourth era where we are out of money so therefore we had to be contract work while we maintain the site that was growing. I met Eoin McCarthy who worked for Hunted and David Lowry who came. By this time we had contacts with Sony and MTV to build serious sites for them. One of the challenges we had was, Twitter showed up, they don't want us building Sony site or doing MTV, what do we do with these people that had been really kind and supportive to us. But we didn't want to leave them in the lurch. But as it turned out luckily, lucky for them — I'm not sure how it plays out. Eoin and David were Irish and they didn't have Australian passports or U.S. citizenship so they couldn't come on the visas. Something was weird with Irish visas at the time. They couldn't come to the acquisition we couldn't support the clients that we had. So they started. The idea was, I said to them: Look it's really you know it's a shame you can't come to Twitter and do the acquisition. But what about you start a company you can have all their clients and see where that takes you.” And that's essentially what happened. They started Hydric. They took over our contracts with those companies and since then I've survived and grow the company. They became specialists are doing services work in the music industry and helping their work with Spotify and community work at Sony and all these other brands in the music industry. I think they joined the last year of Hunted's life as well so they weren't early core members of the team but I would have went with it.

When the acquisition come, when we were negotiating price it was all about headcount — because it was really an acquihire. They weren't interested in keeping Hunted alive. They wanted the biggest engineering team they could have, who knew something about music tech — you know, what you said was true. They were thinking about trying to take on Billboard or Nielsen and they knew it — and they said it multiple times: we think we can build music charts ourselves but people might not believe it. If you come in and build a for us — everyone will believe. So that was really what we were required. So when they launched a competitor to Billboard — which they didn't in the end they did integration with Billboard — they decided to and their whole idea was can we get musicians to equate Twitter activity with success. So, let's do a chat! And when we released this musicians might go "that's a bit mad". But if we acquire hunted and hunted becomes Twitter Music as a chart thing, powered only by tweets then people would go: well, of course this is real, because they liked the other thing. So that was their whole play. And it made total sense to us as well. And we liked that it it was the acquihire, they wanted the engineering, which is their main attraction but there was also some value that we're getting out of Hunted — if only credibility. I could tell that story. And it solves the liability problem for me, of "I never worked out how to monetize it". And they weren't interested in taking that problem on. Pre-IPO, they didn't want to deal with it. So one of the only sticking points we had in the negotiations was I had to dignify Twitter against the music industry, should they come looking for. And, you know, by then the music industry — I only ever had really positive experiences with them. They used the site, loved what it did, found artists, blah-blah-blah. Yeah, I just didn't have any negative experience with that at all.

David Weiszfeld [48:23]: I think that where you got maybe lucky a little is you were just under the scale level where there's just too many people listening to free music. But also it was not just people listening to free music — you were actually helping a lot of people sign. I actually know Phantogram who was signed by Nate Albert — I think Nate used We Are Hunted, from a discussion with him a couple of years back — like some pretty big bands were discovered by Hunted, from pretty big labels. So it's very hard on one hand you're like trying to sign the act that you discovered and then your business affairs like sending a like a lawyer type. You are maybe right at the good spot.

Stephen Phillips [49:01]: I think we were too small. And I think the audience was also really passionate music people. So it wasn't like we were crossing over into top-40 stuff. It was indie, it was cool, it was like, it was music-music people, and I felt like that just "well this is for us". They're not trying to be a massive... I think Grooveshark was the one that blew up while we were there, and they went off to pop and mass-audience and we were like "Oh, good luck with that!".

David Weiszfeld [49:35]: They were going very far, Grooveshark — they were re-uploading songs, they were using torrent and P2P. It was completely another type of scale as well — and I think the philosophy of the company, to be honest.

Stephen Phillips [49:51]: Yes that's right. We were just more into... We were very technical. And we were fascinated by the problem of how you measure virality, or how you measure — like, I've spent way too long and I continue to think about the problem of why do I like this song? I think it's a problem you can work on forever, and it's one of the key ways I still attract young engineers to work in music is why does it do this? What do I like that song and not this song? And how can I do that so easily? How can I click through the radio dial and immediately hear that I like that, when I've heard two seconds of it? What is going on here? Like how does this work? And software engineers, well, the ones who want to work in machine learning find those problems fascinating. And music is the very pure expression of that problem, like what is going on here? How does this possibly work and can we get computers to emulate that? I got fascinated with that at Hunted and so after I left Twitter, that's what I started to keep working on. How can I get better at this? So how can I, how do I solve this problem? How do I stay in that space?