Jump to

- What’s the difference between the Music Industry and the Recording Industry?

- Brief history of sound recording

- The structure of the Recording Industry

- Functions of the Recording Industry

- 1. Scouting for talented artists

- Executive production & Creative Direction

- 2. Producing the record

- 3. Promotion and Marketing

- 4. Distribution

- Licensing and Sync

Record labels are the first thing that comes to mind when people think of the music industry. Even Universal, Sony and Warner are considered “record labels” by the general public — even though their business model spreads far beyond the scope of a “recording company”. Conversely, it’s quite common to put an equal sign between the music industry as a whole and the recording industry — which is not true at all. So, before we get into it, let’s get everyone on the same page.

What’s the difference between the Music Industry and the Recording Industry?

The music industry is a very broad term. Streaming services, sync licensing companies, artist managers, booking managers and event promoters — all those people and companies are a part of the music industry. That's the whole point of our running Mechanics series: to showcase how all those intertwined (but independent) come together, and explain how the music industry actually works — one subset at a time.

The recording industry is a subsection of the music industry that deals specifically with the production (i.e. recording) and subsequent promotion and distribution of music. Record labels are massive stakeholders in the music industry, and in America they’re represented by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

With that out of the way, let's get down to business:

Brief history of sound recording

In the early 20th century, sheet music publishers ran the music industry. House concerts were a centerpiece of middle-class entertainment — the number of pianos manufactured in the US alone averaged at around 300,000 each year (vs. 31,000 in 2017). However, by the 1920s phonographs (and gramophones or graphophones, depending on the brand) became widely available and in 1921 gross sales on the US phonogram market reached $106 million (around $1,5 billion in today’s money) with over 140 million records sold. The first record labels, departments of major phonograph producers (Columbia, Victor and Edison) found their place in the industry as record-makers, financing costly record production, manufacturing and distribution of records.

Just a decade later, at the height of the Great Depression, the revenue shrunk down to $6 million (or $117 million in today's money). The birth of radio, a new music medium which was not only free but also sounded better, lessened the appeal of phonograms. By the 1930s, all of the big recording players in the U.S. were acquired by the radio corporations: RCA bought Victor in 1929 to create RCA Records, and CBS bought Columbia Records in 1939. In 1931, the European affiliates of Victor and Columbia merged to form EMI.

Fast forward through vinyl, cassette tapes, CDs, Napster and digital piracy, download-to-own services and, finally, streaming. Throughout the years, technological advancements caused shifts in the landscape of the industry, as manufacturers of new mediums and hardware took a stake in the record business. Recordings, audio mediums and record-players are what economic theory would call complementary goods. Victor was making records to sell phonographs, and the more phonographs there were, the more was the demand for compatible recordings. Later on, RCA bought Victor to make records that would populate radio waves and therefore boost sales of radio receivers, which, in its turn, grew the radio’s audience and increased demand for new hits.

The same principle carried over to the modern age. Would Apple ever launch iTunes if the iPod wasn’t such a huge success? The synergy between hardware (or, in 21st-century terms, software) manufacturers, distribution channels and the recording side always led to the vertical integration of the recorded music chain. We can see the signs of this tradition in relationships between the record companies and streaming services today. Remember how Frank Ocean released Blond? Back it 2016, he delivered his visual album, Endless to fulfill contractual obligations to Def Jam and Universal — and release the “proper album” on the next day via his own label as an exclusive for Apple Music. Shortly after, Universal announced that it would no longer do streaming exclusives, and although it’s still not clear if these two stories are related, the tensions within the recording chain are apparent.

The structure of the Recording Industry

The record industry is guided by technology, more so than any other part of the music business. Getting a record from the studio to the final customer used to be a lengthy and costly process. Now, an album can be produced on a laptop, and digital distribution via streaming has a zero marginal cost — the structure of the recording chain itself has radically changed.

In the age of physical distribution, it was reasonably straightforward. Major labels were recording and marketing, manufacturers were producing physical media, distributors were taking care of the logistics, and record stores were facing the final consumer. The digital environment has turned that system upside down. Now, customers get music via digital service providers of all shapes and sizes, from ad-driven video platforms such as YouTube to customizable digital radio of Pandora and subscription-based streaming services. Recording artists sign with labels and labels work with distributors, who collect recording royalties from DSPs. However, almost every step of this chain can be bypassed altogether.

Artists can release their music directly on platforms like Soundcloud, Bandcamp and, as of late, even Spotify or sign a “distribution only” deal to put their music on all digital platforms – and keep most of the revenue for themselves. Nevertheless, labels are still at the heart of the industry, and they were able to keep that position by continuously adapting to the evolving realities of the market.

You see, even if the artists can record an album and make it available all over the globe at next to no cost, they still need some "music bank" to finance the release promotion — that's just the way the recording economy is arranged. We get down to this very topic in our latest analysis of the release cycles, where we follow the money and break down exactly how labels and recording artists make money using our custom built revenue projection model. Check it out to see how the recording dollar is (actually) split under popular recording deal types, and how this balance affects the music industry as a whole.

Functions of the Recording Industry

The record business has three primary objectives:

- Scout for talented artists

- Produce records: funding the recording process and helping develop the artist’s sound and image

- Promote artists and releases across all channels while designing, implementing and financing marketing campaigns.

- Manufacture and distribute the record

The first three objectives are the focus of all record labels, although throughout the years the priorities between the three have shifted — don’t worry, we will get into it a bit later. The fourth function, manufacturing and selling the record, is a job of distributors. However, some labels (mainly the majors) can internalize that process and distribute themselves — which is in fact one of the main qualitative distinctions between the major and independent from recording standpoint.

1. Scouting for talented artists

Almost every record company has some sort of Artist & Repertoire department, or simply A&R. It can be limited to talent hunting or work hands-on with artists on everything from image to creative team composition. A&Rs come in all shapes and sizes — but their primary goal is to find promising artists and sign them to a label.

Scouting for talent has changed a lot as the digital space took over the music industry and recording technologies made the production process affordable. Back in the day, labels were talent hunters that had to bet on an inexperienced, unproven artist coming out with a successful debut. That meant significant recording investments without any real guarantee of returns — but massive record sales of the biggest hits made up for that risk.

Nowadays, upcoming artists record their debuts without the label’s involvement. First tracks or even albums are recorded in bedrooms and garages. Initial fan-bases are built on social media, which have become the hunting grounds of most A&Rs. If labels used to make records, now they find them — and the first label deals are signed when artists have recorded and released music by themselves.

In contractual terms, this is the shift from the artist deals to the licensing ones. Under an artist deal, the label pays the artist in advance and finances the entire release cycle to own lifetime copyrights of a final recording. Licensing deals, on the other hand, are signed when the artist licenses an existing record, contracting copyrights to the label for a specified period (and, sometimes, a specified geographical market). Such deals are less risk / more costs scenario for the record industry: on the one hand, the label has to invest into “buying” an existing (and somewhat successful) record, but in exchange, the risks of the creative stage are avoided altogether.

Executive production & Creative Direction

However, finding talent is just the first part of the A&R’s job. Once the deal is done, A&R representatives continue working with the artists. On the production side, they offer input on overall creative direction and help build the creative team: finding songwriters and songs for artists who don’t write their own material, putting rappers in touch with “hot” producers and beatmakers, and so on.

On the artist development side, A&R becomes something like a brand manager for the talent. What kind of photoshoots should the artist do, how the album cover should look like and what will be the music video aesthetic? A&R can help find answers to such questions, defining the artist’s image and positioning and laying the ground for the future marketing strategy, carried out by the label’s promotion team.

As we’ve already mentioned in the Mechanics of Management, usually the manager is also heavily involved in the artist development process. That means that artists, A&Rs and managers have to be aligned for the chemistry to work. This is not always the case, however — so there’s often a bit of a power struggle between the management and A&R, which can go either way. When it comes to the artistic direction, the A&R can be limited to the administration of the recording process or end up running the artist’s career — the extent of A&R’s involvement is unique to each artist.

2. Producing the record

Production of the master record is an intricate process. The creative process is unique for each artist: some don’t need anything but their laptop to record, and others require a symphonic orchestra, a choir, hundreds of mixes and several studios. The costs of making an album can fall anywhere between 0 and infinity: Nirvana’s Bleach was notoriously recorded in 3 days on a $600 budget, while Guns N’ Roses’ Chinese Democracy cost around $13 million and took over 13 years to make.

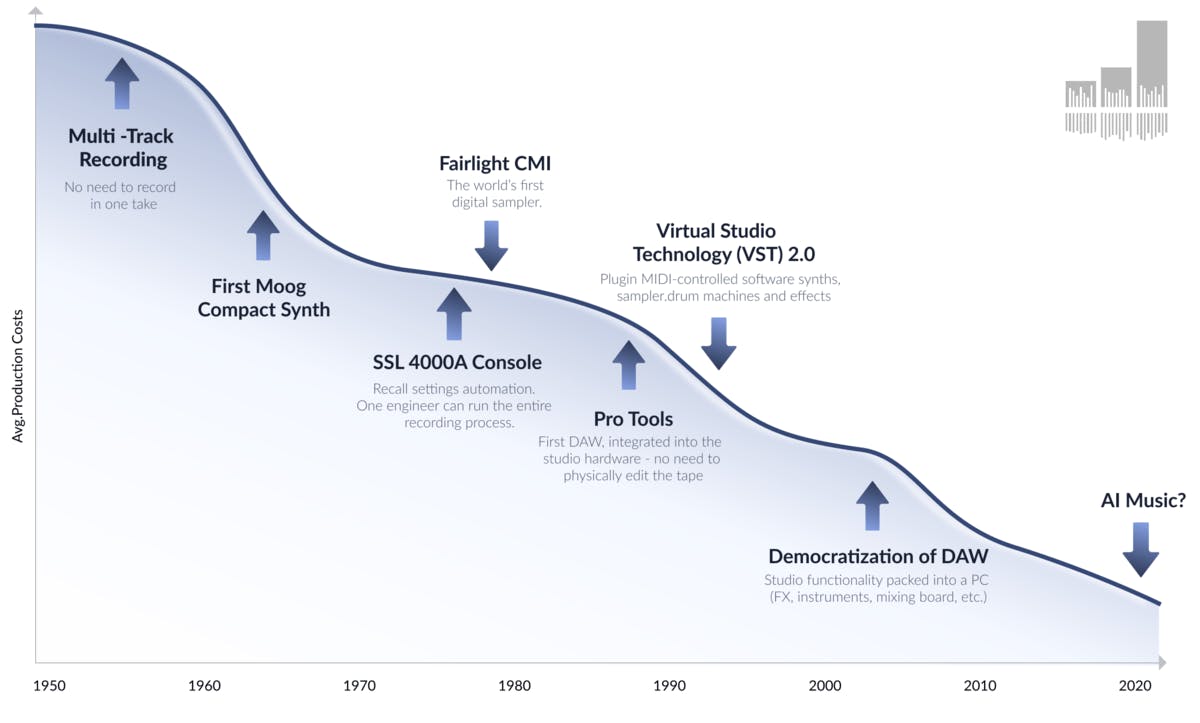

However, if we take the outliers out of the equation, an average recording investment has unquestionably diminished over the years. From the invention of the 8-track machine in the 1950s, that allowed mixing several sound sources to create a final recording, to the modern-day Digital Audio Workstations that pack functionality of a fully-fledged record studio into a single laptop, technology optimized the recording process, making it both cheaper and more accessible.

Assumed Average Production Cost Timeline, 1950-...

This is a massive shift in the recording business. The label’s endorsement used to be a must for an artist to record music, and now, funding the recording process is just another bullet point in a long list of label’s services. Some artists still need to rent a studio, pay for technicians, gear and session musicians, and label finances that process — but it’s not an integral part of the business anymore. Owning a full-scale record studio is extremely rare amongst the labels of today, while throughout the 20th century all majors labels kept dozens of engineers on the payroll. The record industry is no longer here to record, but rather to find upcoming artists and help them develop careers and build audiences.

3. Promotion and Marketing

So, as the costs of production were cut down a lot, labels had to adapt, shifting their focus from making records to promoting them. The principal part of the label’s service is now promotion, marketing, and distribution of the release, and the licensing deals are an implication of that shift.

Promotion and marketing are pretty much the same in their core as they share an end-goal. The main difference is that marketing involves directly paying for the reach and the audiences, while promotion strategy is all about getting media and fans to talk about the artist "for free". At large, promotion and marketing strategies are mostly business as usual: put out singles and pitch them to playlist owners and radio programmers to get initial play, try to persuade music journalists to cover the release, and once the record is out — buy ads, and book TV and radio appearances.

Labels have connections with both traditional and digital media, from radio, TV and press to blogs and online outlets, and in that sense not a lot has changed since the 60s. Although the media-space has become more diverse and leveled across the board, networking still plays a crucial role in the industry. Just like in real life, a recommendation from a friend can go a long way — there is a difference from a journalist’s standpoint between getting a press release from an unsigned artist and a PR-manager they know and trust.

Those communication strategies, of course, depend on the scope of the artist, but the basic principle remains the same. The media have evolved and hundreds of new channels and formats became available to the marketing team. However, the end goal of the label is still to make more people talk about, listen to and buy the record.

4. Distribution

In the old days, getting audio from the studio and into the ears of the listeners was a complex process of setting up and optimizing the physical production and logistics, that relied on a network of subcontractors and partners. Then, the digital age came around, rendering the old system obsolete, and the distribution suddenly became much, much cheaper. Now, you could simply upload music on a digital platform — and make it instantly available to fans from all over the globe. However, distribution still plays a huge role in the recording business.

A good distributor should not only make your music available across the DSPs, but also make it more visible on the platform. We've covered music distribution in a separate article, so head out there if you want to know more about how this subset of the industry works.

Take me to the Mechanics of Distribution.

Licensing and Sync

There is one last part of the record business that we’ve decided to keep out of scope for now: integration of recordings into other creative products, like movies, video games and so on. Much like distribution via streaming platforms, content synch can become not only a healthy revenue source but also a vast promotion channel. There are dozens of artists who have broken the charts after a single successful integration.

Sync licensing is a tricky subset of the industry, which affects both the publishing and the recording companies, as well as stand-alone licensing reps, music supervisors and production companies. To find out more about how the sync licensing works, check out our Mechanics of Sync Licensing.